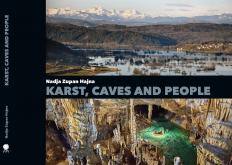

The karst regions of Slovenia, like those in many other parts of the world, result from the rock being limestone which is slightly soluble in rainwater. This not only causes a lack of surface streams and the presence of caves and underground rivers, but also other features characteristic of karstic landscape. In particular, solution of intersecting fissures in the rock results in cone-shaped depressions – dolines – in which some residual soil collects, and more is sometimes added by farmers to allow cultivation. Bigger, often vertical-sided depressions called collapse dolines result when the ground surface collapses into caves or cavities formed by underground streams. Collapse dolines include the immense pits at Škocjanske jame.

What is unusual about Slovenia is the amount of karst terrain that it contains. 43% of the whole country is karst; and of the part of Slovenia which was the old Austrian region of Carniola or Krain (Gorenjska, Dolenjska and Notranjska, including the Postojna area), 69% is karst.

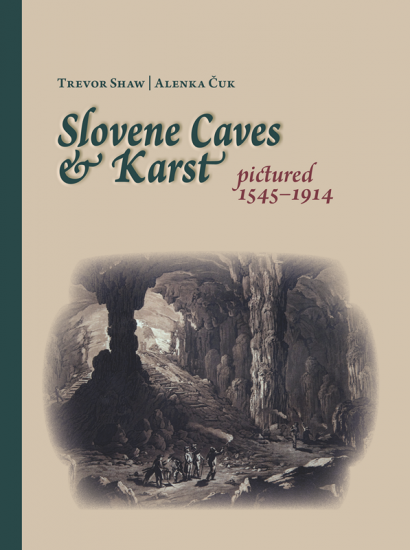

The caves and spectacular features of karst have for centuries appealed to visitors and travellers, as they do to tourists today. For much the same reasons they have appealed to artists whose desire was to capture the scenes for themselves and for posterity.

Over the last two centuries or so we have become more and more accustomed to images of the real world. In modern times natural history films have become almost a substitute for the real thing. Personal cameras record what we have seen, sometimes more reliably than our memories, and magazines as well as television provide accurate pictorial information.

But it was not always so. Some five and a half centuries ago, printed books began to appear, providing information for those who could read. At first very few were illustrated, but about 430 years ago Valvasor was already producing his book on the castles of the province of Krain, illustrated with copper engravings; and ten years later, in 1689, there appeared his great topographical book on Krain, containing 535 illustrations. Painters of course did not depend on books to have their paintings displayed. But in later times their work was reproduced in books and reached a much wider audience.

At the same time, as technical developments made such reproduction easier and cheaper, the population increasingly learned to read. Poverty overall reduced and more people were able to enjoy leisure. This, with education, allowed them to use books and to see pictures other than those in the stained glass windows of churches.

This broadening of the kinds of readers, as well as an increase in their numbers, led quite early in the 19th century – only two centuries ago now – to the appearance of popular illustrated books aiming to arouse and satisfy curiosity. Titles such as The Wonders of Nature and Art (1803) and The Hundred Wonders of the World (1818) make this clear. Such books often include cave descriptions, many of them illustrated, and it was in this way that people living in non-karst regions became aware of the existence of caves.

So much for generalizations and context. What did all the images aim to do? One or more of the following, surely: to express the impressions, emotions and feelings of the artist; to inform people about caves and karst features; to give pleasure, by beautiful paintings or by luxurious albums of engravings; to illustrate texts (travel books, regional descriptions and guidebooks, scientific studies, accounts of cave exploration, historical studies, studies of cave images); to publicise particular caves and to advertise an unrelated product by an attractive picture.

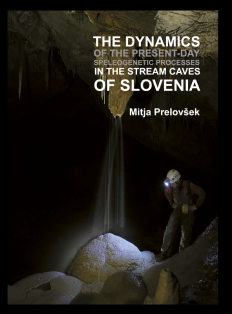

Whilst scientific or geographical studies may require images of little-known caves or phenomena, it is clear from the content of this book that certain caves were more often the subject for artists and photographers than others. Several factors are responsible for this. Clearly an attractive cave, as the very word denotes, attracts more attention. A picturesque scene attracts pictures. And such pictures attract purchasers.

Also relevant is the extent to which the cave or place is already known. The better known places will be visited by more artists and photographers, and by more potential purchasers. Purchases, of course, include not only individual images but also illustrated guidebooks.

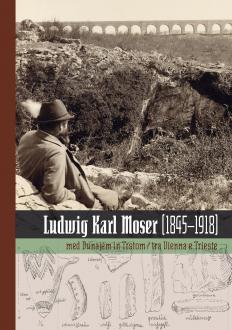

Another factor besides picturesque beauty affected this popularity of a place, especially before the motor car became widely available. That was its location and ease of access for large numbers of people. For Slovenia, many potential visitors were to be found at Trieste (as a major part where they waited for their ships) and on the main routes such as the vital road from central Europe through Postojna to the coast. Hence the popularity of Vilenica, Škocjanske jame and Postojnska jama. They attracted the artists and photographers, and they also attracted the visitors who would buy their productions.

Among the many cave images known, some (only a few, but nevertheless some) do provide information that is historically important. Dress is necessarily shown wherever there are people. That of the visitors is normal for the period and sometimes it is the dress that helps to date the image. Images of cave entrances necessarily record whatever barriers, gates, seats or buildings that were present at the time.

The earliest images of karst features occurred on 16th century maps, where the land was represented, not by accurately surveyed rivers, roads and contour lines, but by pictorial representations. Some of these were symbolic, such as trees for forests and little hills for mountainous county. But special features (and Cerkniško jezero was certainly considered very special) were drawn individually and the space required for this gave them extra prominence.

Individual pictures were sold for display, as indeed they still are. Such engravings were sometimes published together in albums, with or without text, as fore-runners of modern coffee-table books. The emphasis there was on attractive images, whereas later in the century pictures were used to illustrate points made in the text, for example in the books of Martel and Kraus or to illustrate places described in guidebooks.

Engravings, where the artist’s image was redrawn by the engraver on a metal plate (or lithographs where it was redrawn in stone) were still used to illustrate books and magazines up the 1890s. In that period the “artist’s image” to be engraved was often a photograph. Only when the half-tone process was developed in the 1880s, was it possible for photos to be transferred mechanically to paper in large quantities without an intermediate process.

In those earlier days (1870s to 1890s) photographs were usually engraved for publication. But the reverse also occurred. Photographers realized that cave pictures were saleable, but they found also that they were very difficult to take.

Copying was not only done to facilitate reproduction of images. It also occurred, without acknowledgement, when the easiest source for a new (saleable) illustration was an earlier one. In book publication (and ship capture) this is termed piracy. It was common in the 19th century and several examples are exposed in this book.

Of course, cave images of quality continued to be made after the cut-off date for this book – the start of World War I and the end of Slovenia’s time as part of Austria. Photographers include Friedrich Oedl (1894-1969) at Škocjanske jame in 1921, Franci Bar (1901-1988) in many caves, and several members of the Društvo za raziskavanje podzemskih jam. All those photographers were cave explorers themselves. Painters of this later period include Leo Vilhar (1899-1971); Mario Vilhar, his son (born 1925), and Lojze Perko (1909-1980).

paperback 20 × 27 cm 338 pages more than 200 illustrations

Keywords

artistic motives | karst caves | karstology | monographs | painting | speleology