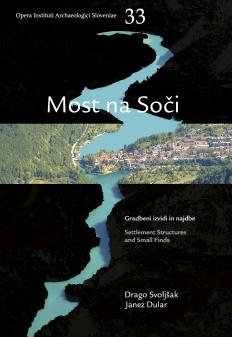

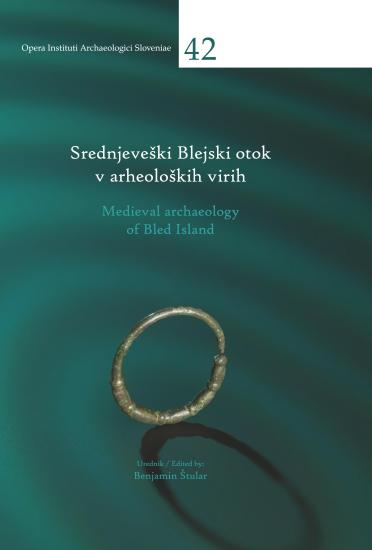

The book Medieval Archaeology of Bled Island is presenting the results of a state-of-the-art archaeological analysis of data from archaeological excavations of the 1962 and 1964.

Polona Bitenc and Timotej Knific analysed of the archaeology of material culture, while Benjamin Štular focused on the archaeology of individuals and communities. The very poor state of preservation of the bone archive meant that an anthropological analysis could not be included on an equal footing with archaeological data in the process of interpreting the site (Leben Seljak). A broader perspective follows, placing the new findings are placed in the context of the archaeological landscape of the Bled micro-region (Pleterski). Important for the book are the results of the excavations near the village of Bodešče (Modrijan).

Two key scientific questions were asked in the book: Did a pre-Christian sanctuary exist on Bled Island? What was the chronology of the churches?

From this it can be concluded that the supra-local object of pre-Christian worship on Bled Island was a spring. Judging by the analogies from written sources, the spring was surrounded by a grove or at least lay in the shade of a tree. Ritually connected with the spring was a nearby place marked with a rock. There is no direct archaeological data on when this situation was established, but it can be assumed with reasonable certainty that this part of the Bled Island was already of special importance in prehistoric times.

At the beginning of the 10th century, a small community began to bury their dead on the island. The original organization of the cemetery symbolically connected it with the spring, which was worshipped on the island, and with the central location of the the Early Medieval burial landscape, the Višelnica bonfire site. The locations for the burials of the first generation were carefully chosen near the fireplace, where the fire burned for at least part of the funerals. The following three generations buried their dead according to changed rules: the graves were arranged in rows, some were oriented towards the true East thus exhibiting considerable astronomical knowledge and. The last grave in this cemetery was dug in the first decade of the 11th century, and its orientation corresponded to the orientation of the first church.

In the first decade of the 11th century, probably after the formal acquisition of the property by the bishops of Brixen in 1004, a small wooden church was built on the island, dedicated to St. Mary of the Assumption was built on the island. A burial under the threshold, the guardian of the entrance, offered the church symbolic protection. Despite the apparent modesty of the church, some state-of-the-art architectural and astronomical knowledge for the time were incorporated into the construction of the church. After only a few decades, the original wooden church was demolished and replaced by a somewhat larger and finer building. This church was also protected by the guardian of the entrance. To the west of the church, in the shadow of the sunrise on the day of the Assumption, a very small community of mixed gender and age began to bury their dead. The community was orthodox and conservative, which is reflected in the strict observance of the same rules for Christian burial for almost two centuries. These characteristics, together with the exceptional location of the cemetery on the island, place this community within the circle of persons belonging to the administrative and defensive apparatus of the Bishops of Brixen.

After almost a hundred years, perhaps in the second decade of the 12th century, the wooden church was demolished and construction of a new stone church began. This was a relatively ambitious Romanesque architecture which completely changed Bled Island its appearance: what was an island with a small church near a spring in a grove became a church on an island. Immediately east of the altar of the new church, in the holiest place in the Christian world (usually reserved for saints or at least bishops), a non adult person was buried. The continuity with the old church was reflected in the burial of the third guardian of the entrance and the other burials west of the church.

The archaeological data agree well with the historians' interpretations, which refer to the deed of donation of 1004 and the consecration of a church in 1142. However, it is worth noting that an excellent degree of congruity between archaeological and historical interpretations does not make any of them more solid. Since these interpretations are based on completely different sources, they remain separate, each only as solid as the arguments that support it.

Large format field drawings are available at: http://iza.zrc-sazu.si/pdf/Opera/OIAS_42_2020_12-5.pdf

hardback 20 × 29 cm 392 pages 63 figures, 12 drawings, 12 maps, 51 plans, 12 tables and graphs, 34 tables

Keywords

anthropology | archaeological sites | Bled | Bled Island | building analysis | cemeteries | churches | Early Middle Ages | Middle Ages | morphometry | mythical landscape | stratigraphy